Hayao Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli Films Feature Unparalleled Girl Power

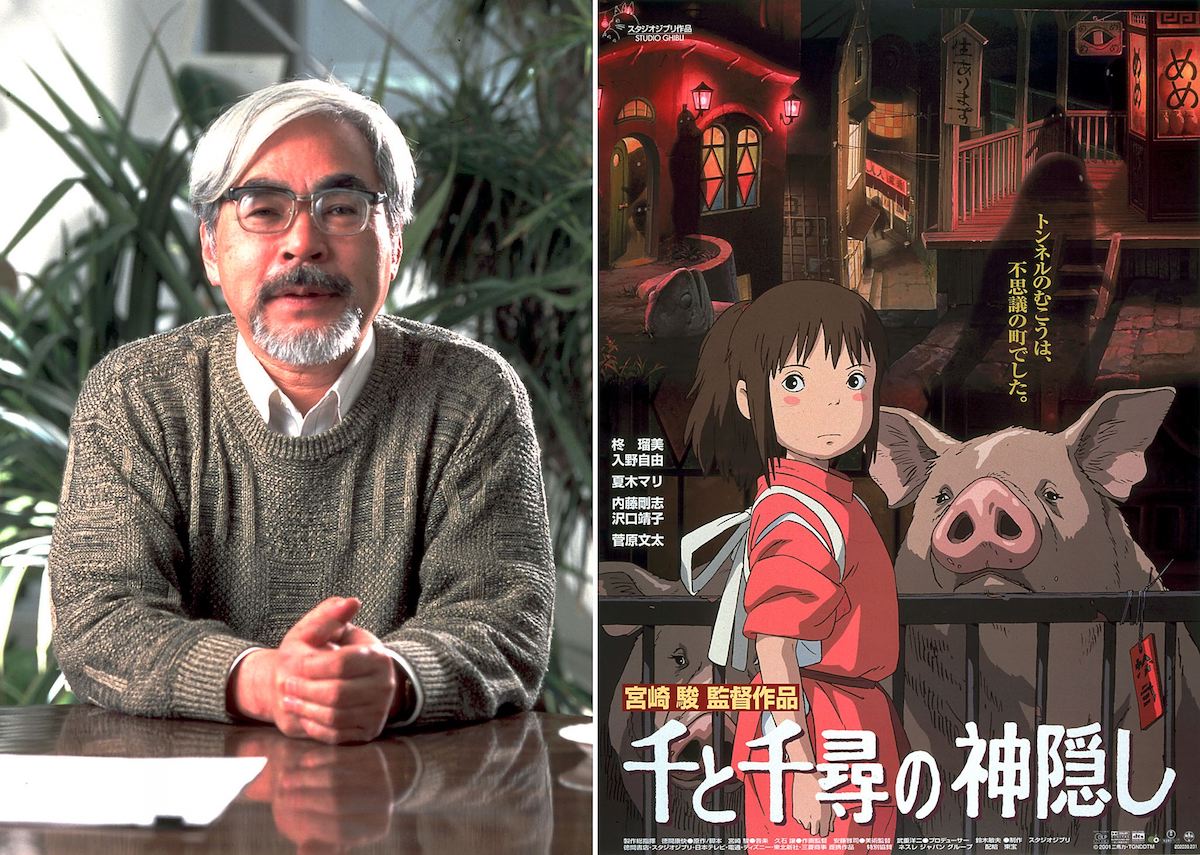

Among the many intricacies in Hayao Miyazaki’s movies, one not-so-subtle feature is his placement of girls and women as central characters. From Kiki to Chihiro to Ponyo, we’re taking a look at how the groundbreaking Japanese auteur celebrates the spirit of the strong female lead.

Miyazaki’s princesses are ferocious and independent

Vice reported in 2016 on how Miyazaki drew on “girl power” to drive many of his films. And it was never in a conventional sense; his female characters are either gritty warriors or awkward youngsters, trying to find their way toward wisdom and independence.

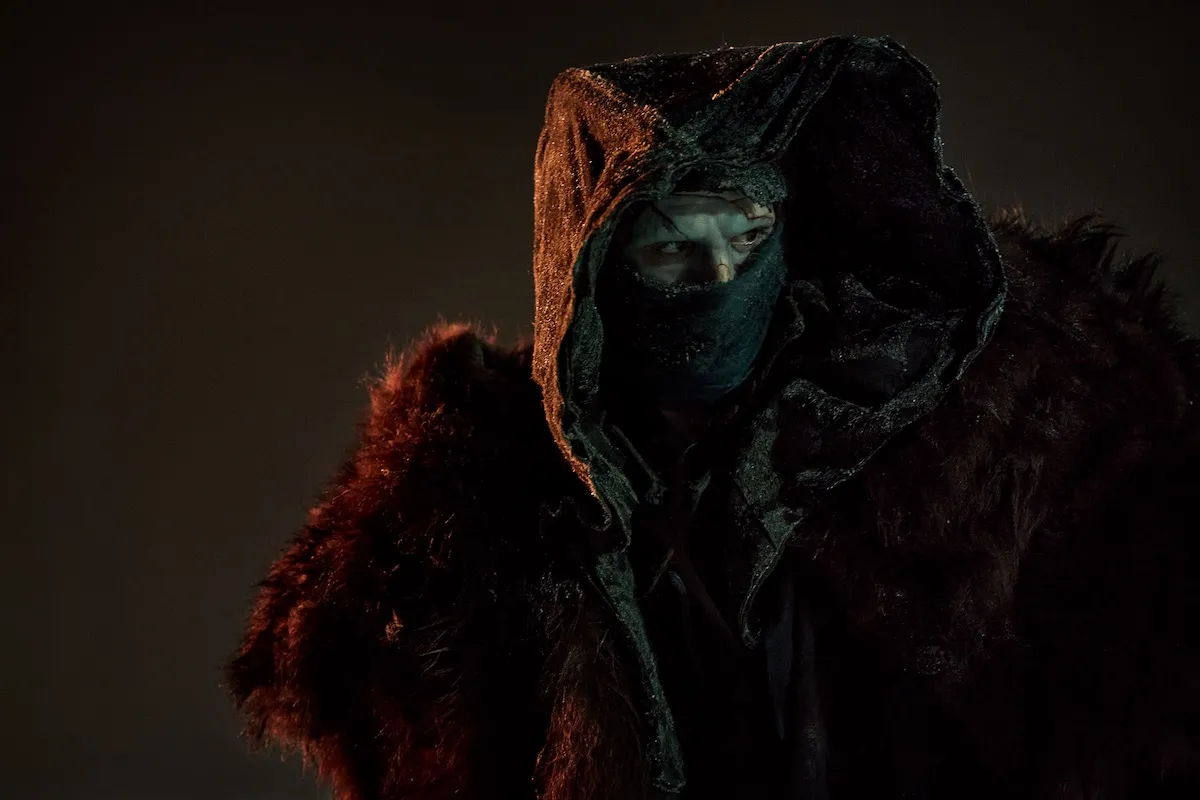

It’s not a stretch to see how his masterful works of anime differ from the pop-culture fare offered up by Disney or Pixar. Yes, there are occasionally princesses–but Princess Mononoke (1997 Japan/1999 U.S.) isn’t conventionally “pretty.” She’s a wolf-back riding warrior who ferociously protects her forest-home. Vice noted that when “San” comes face to face with Prince Ashitaka, she doesn’t fall instantly in love. With a blood-covered face, she sizes him up silently–and then commands him to leave.

The title character from Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984 with a U.S. release in 2003) is also a princess; a skilled fighter who wears a gas-mask and possesses the ability to communicate with the monstrous insects that populate her world. Her mission is to save the Valley of the Wind, just as San protects her magical woods.

Many of Miyazaki’s lead characters are awkward girls seeking independence

In the Academy Award-winning masterpiece Spirited Away (2001), lead character Chihiro is a slightly spoiled 10-year-old girl. Her boredom with life is cured in an instant when she becomes both homeless and orphaned. Upon wandering onto forbidden land, her free-spending parents are turned into swine and Chihiro is forced to find a job at a bathhouse populated by bizarre spirits and talking animals. She must find a way to save her parents; a massive responsibility for a child. She’s befriended by Haku, a 12-ish boy who periodically transforms into a tormented dragon. Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989 with a 1998 U.S. release) is the story of a 13-year-old girl who leaves home to train to be a witch–a terrifying prospect for any parent of a daughter, but Kiki triumphs, making lifelong friends in the process.

Ponyo is in a class by herself. The plucky, 5-year-old ham-loving goldfish/girl haplessly escapes from the ocean. A 5-year-old boy, Sōsuke, rescues her and the two become fast friends. She wants to become human, but her ability to perform magic has complicated things.

At just 5, Ponyo is perhaps the most striking example of one of Miyazaki’s “independent” girls. But at a range of ages, they all represent a strong female presence, searching for something greater than themselves.

“Many of my movies have strong female leads- brave, self-sufficient girls that don’t think twice about fighting for what they believe in with all their heart,” Miyazaki told The Guardian in 2013. “They’ll need a friend, or a supporter, but never a savior. Any woman is just as capable of being a hero as any man.”

Falling in love is not the end goal

While in Spirited Away, Chihiro finds an innocent sort of love with Haku, she doesn’t do so before going on a profoundly lonely journey. By the time she discovers her love for Haku, in a subversive twist, she is the one who rescues him. He’s trapped in a spell and can’t remember his name.

Princess Mononoke (San) never does embark on a romance with Ashitaka; the two ultimately part ways completely. One of Miyazaki’s more overtly romantic films, Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), has Sophie and wizard Howl falling in love–but again, not before she saves him. Females saving males is a repeat twist in Miyazaki movies. And the love that remains, if not romantic, is always pure.

“I love Ponyo, whether she’s a fish, a human, or something in between,” says Sōsuke. And that, perhaps, is the very heart of a Miyazaki anime film.