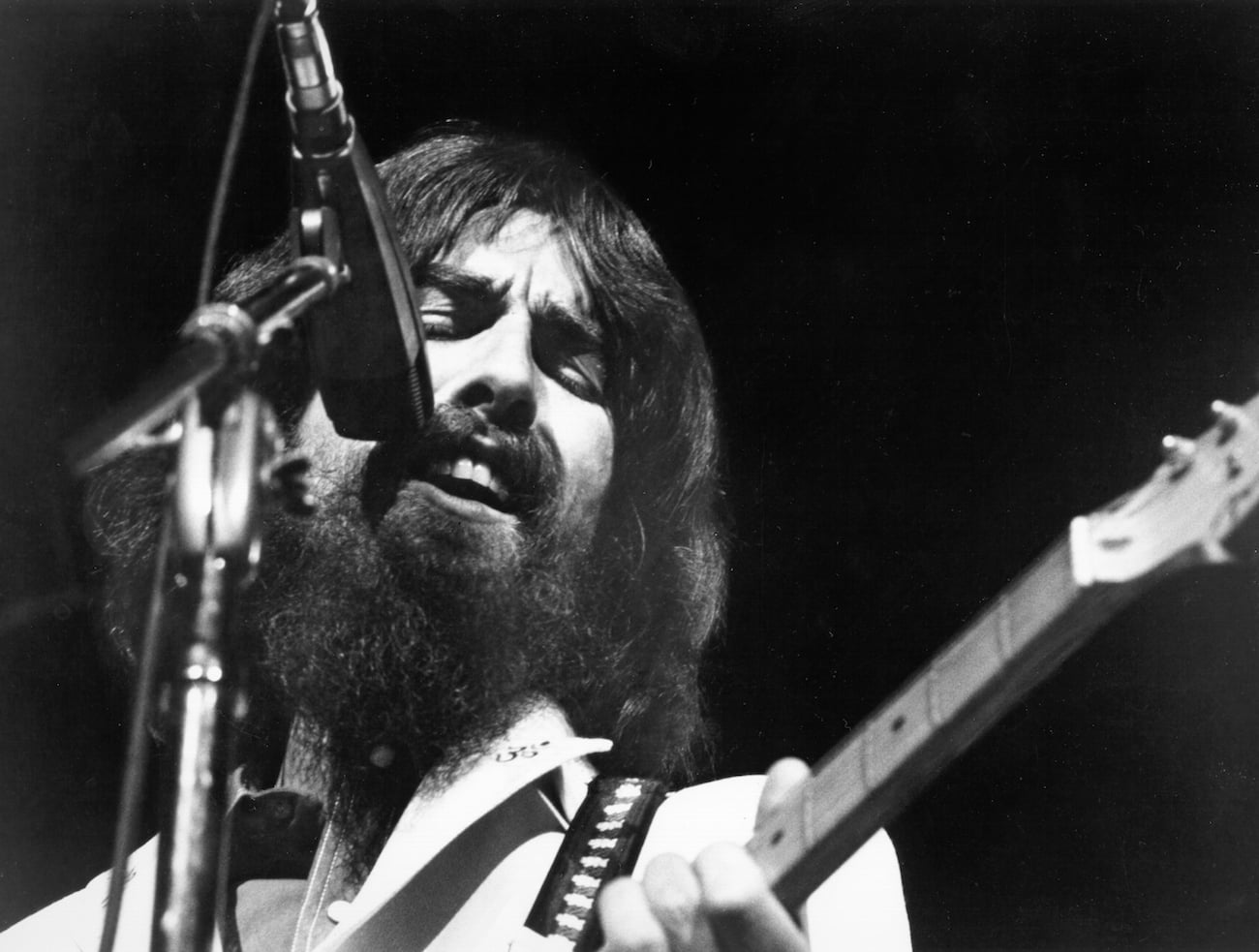

The Musicians Who Performed at the Concert for Bangladesh Called George Harrison ‘Mr. Professor’ or ‘Curly Toes’

The musicians who performed at the Concert for Bangladesh called George Harrison “Mr. Professor” and “Curly Toes.” The former Beatle was nervous about the benefit concert and prayed it all went OK. He gave his friends a noble speech before the day of the show.

George Harrison organized the Concert for Bangladesh in a few weeks

In late 1971, Shankar told George about the humanitarian crisis in East Pakistan.

A devastating cyclone had killed 500,000 people. After months of inaction from the West Pakistani government, people wanted a change. Eastern nationals declared themselves the independent country of Bangladesh. It started a bloody war. The Western Pakistani troops committed genocidal acts on the Bengali people.

In 1997, Shankar told John Fugelsang at VH1 (per George Harrison on George Harrison: Interviews and Encounters) that he’d started planning a benefit concert himself. He expected to raise about 20 to 30 thousand dollars. George believed he could do better.

“The more I read about it and understood what was going on, I thought, ‘Well, we’ve just got to do something,’ and it had to be very quickly,” George told Fugelsang. “And what we did, really, was only to point it out. That’s what I felt.”

George’s former bandmate John Lennon gave him the confidence to begin organizing the benefit concert.

“I think that was one of the things that I developed, just by being in the Beatles, was being bold. And I think John had a lot to do with that, you know, cause John Lennon, you know, if he felt something strongly, he just did it.”

George consulted an Indian astrologer to find the perfect date for the benefit concert. He set it for August 1, 1971, at New York City’s Madison Square Garden.

The musicians who performed at the Concert for Bangladesh had hilarious nicknames for George

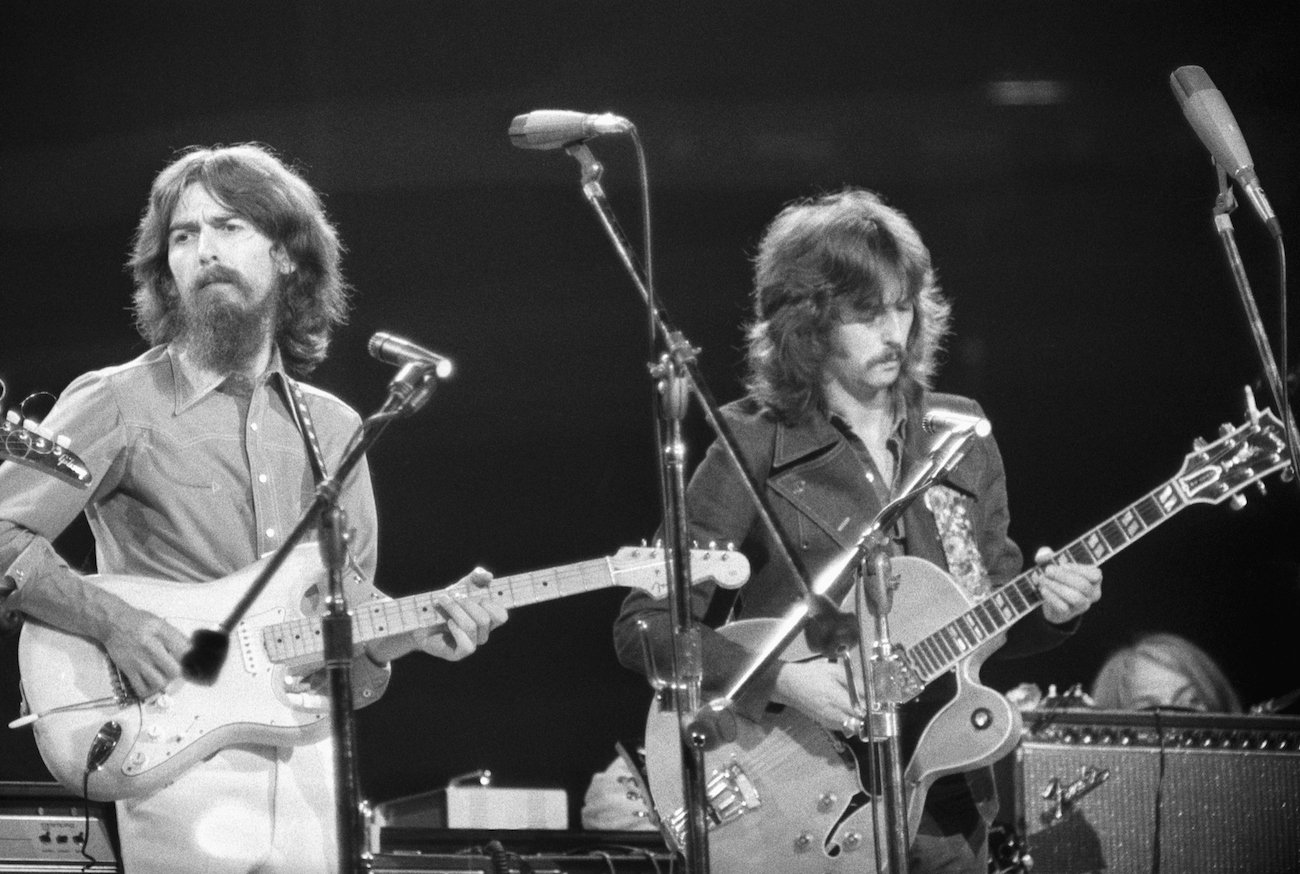

George organized the Concert for Bangladesh in a few weeks with some of the best rock stars set to perform, including George’s fellow Beatle, Ringo Starr, Leon Russell, Eric Clapton, Billy Preston, Badfinger, and Bob Dylan (who was a no-show right up until the last minute).

This would be George’s first live show since The Beatles broke up, an “uncomfortable position for someone

striving to chip away at ego,” Joshua M. Greene wrote in Here Comes The Sun: The Spiritual And Musical Journey Of George Harrison.

Bassist and friend of The Beatles, Klaus Voormann, said, “George was very nervous, but he got this strength through his friends and his religion. His view was ‘It’s my gig, I have to do this. . . .’ If it wasn’t for the cause, he wouldn’t have done it.”

George reserved rooms at the Plaza Hotel for the arriving troupe of musicians coming into New York City for the benefit concert. When they all arrived, George said he wanted the performances to run smoothly. This was their chance to make a difference.

“They clapped each other on the back, stoked a boiler of excitement, and energized one other with a shared sense of mission,” Greene wrote. “What he envisioned, he told them, was a dignified concert, spirit in action, a happy thing that would be very much worth the effort.

“When George’s philosophizing threatened to spill over, the musicians poked affectionate fun by calling him ‘Mr. Professor’ or ‘Curly Toes,’ referring to the pointy plastic shoes that Indian gurus sometimes wore.”

George acted as if he was rallying the troops. All the performers were a “unit” with George as their “engine.”

The former Beatle pep talk was inspiring

George had days to organize the Concert for Bangladesh, but it turned out to be a great success. Nothing like it had been down before. The former Beatle began the first show with a set from his musical guru, Shankar, and then started a string of his own work.

“There was a logical chronology to his choices, starting with ‘Wah Wah,’ which declared his independence from the Beatles; followed by ‘My Sweet Lord,’ which celebrated his internal discovery of God and spirit; and then ‘Awaiting on You All,’ which projected his message to the world. If you just open your heart, the song declared, you would see that you’ve been polluted,” Greene wrote.

George’s pep talk seemed to have worked.

“Nothing was of his creating, George reminded himself, certainly not the results of the concert. He wanted to work in a spirit of detachment, content to know that a wiser force guided the gears and cogs of his life. If he woke up tomorrow and found that the concert had changed nothing, so be it—he would have done his

best.

“But he couldn’t stand by and watch people killing each other. Where was the spirituality in that? That’s what he’d told the artists, and thank God they’d responded, especially Dylan. They’d played, all of them, with compassion for people none of them knew, halfway around the world, purely because they were human beings in need of help.”

Millions were donated to help the refugees, and George made history as the first person to organize the first benefit concert. George would’ve done anything as long as he did something. He even put up with his friends’ good-natured nicknames.