Bob Dylan’s Fans Thought His ‘Dirty, Vulgar’ Backing Band Was ‘Killing’ His Career

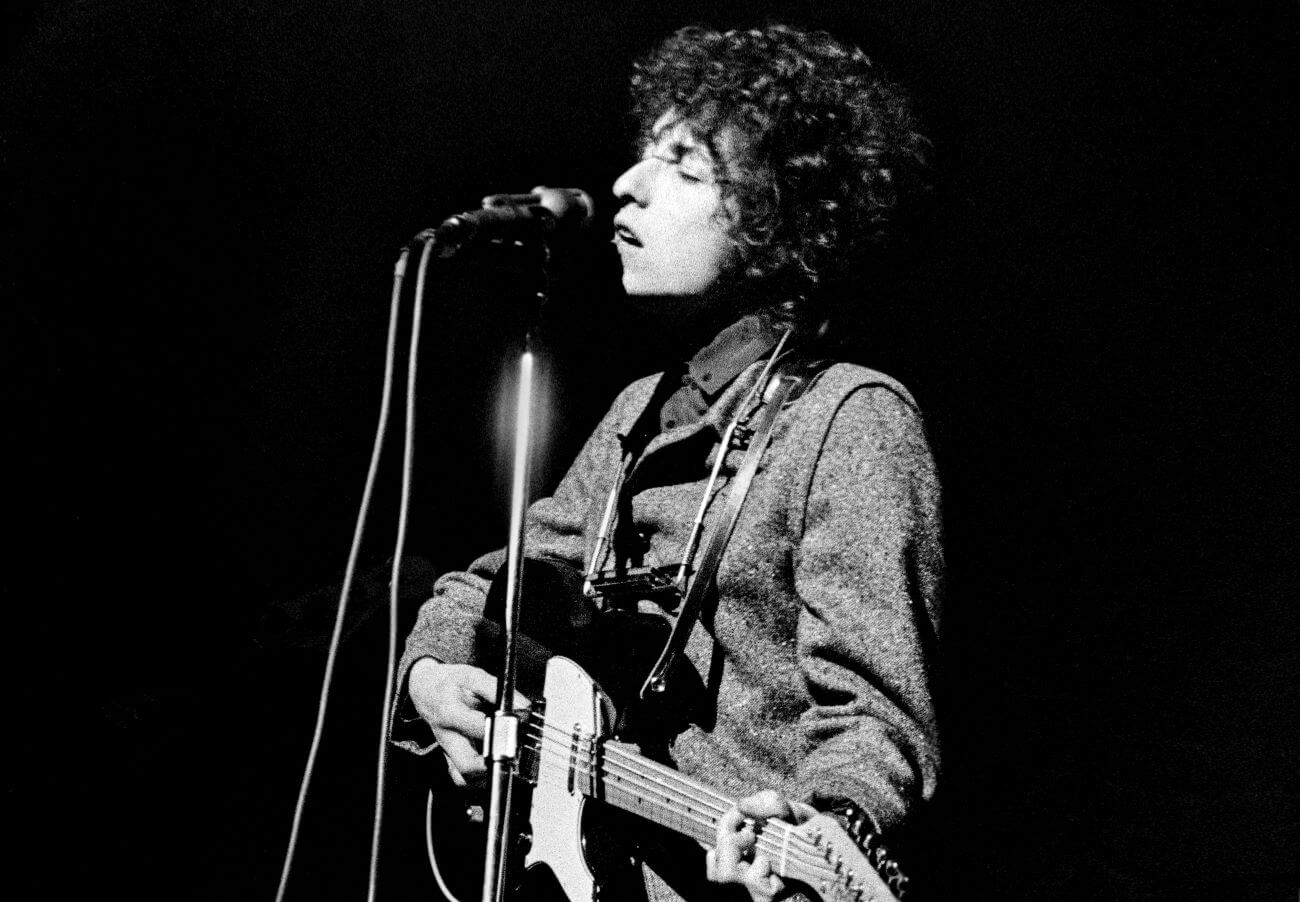

In 1965, Bob Dylan’s fans felt their favorite artist had committed the ultimate betrayal by going electric. Dylan had grown bored of the folk scene and wanted to grow as a musician. His fan base, unfortunately, didn’t think this was a good move. While fans booed Dylan during concerts, they couldn’t bring themselves to completely turn their backs on him. Instead, they directed their anger at his backing band, the Hawks.

Bob Dylan’s fans did not like his backing band

Dylan hired Levon and the Hawks, a Canadian group, to back him in live shows. He already knew his audience wasn’t exactly receptive to electric shows; they’d famously booed him at the Newport Folk Festival. When he asked the Hawks to back him, they weren’t sure how it would go.

The answer, they soon found, was not well. Audiences booed throughout the performances, calling Dylan a traitor. People still attended the shows, but audiences at various venues made their frustration clear.

“The audiences kept booing,” drummer Levon Helm wrote in the book This Wheel’s on Fire: Levon Helm and the Story of the Band. “We made tapes of the shows and listened to them afterward in the hotel, because we couldn’t believe it was that bad that people felt they had to protest, but the tapes sounded good to us. It was just new.”

Soon, Dylan’s fans shifted their frustration to the Hawks. They were the new, electrified component of the shows. People began telling Dylan to dump the group.

“Meanwhile, people out front were yelling, ‘Get rid of the band!’ and backstage, people were coming up to Bob and saying — right in front of us sometimes — ‘Look, Bobby, these bums are killing you. They’re destroying your career. You’re gettin’ murdered out there. Why do you wanna pollute the purity of your thing with this dirty, vulgar rock and roll?'”

Bob Dylan didn’t care about what his fans had to say

While Dylan’s fans made their feelings clear, he didn’t care. He felt shaken the first time a crowd had booed him. After a while, though, it just strengthened his resolve to play rock music.

“The more Bob heard this stuff, the more he wanted to drill these songs into the audience,” Helm wrote. “I mean, he was on fire. We didn’t mean to play that loud, but Bob told the sound people to turn it up full force. We were the first rock band that played in some of these old arenas and coliseums, and Robbie’s guitar used to reverberate around the big concrete buildings like a giant steel bullwhip. It was intense. Bob was hot-wired into it.”

Dylan also appreciated the media coverage that came from getting booed in every one of his shows.

“I wish they had booed,” he said after playing a show with a more forgiving audience. “It’s good publicity. Sells tickets. Let ’em boo all they want.”

Levon Helm said he had a harder time dealing with the audience reaction to his music

While Dylan gleefully courted his fans’ anger, the Hawks had a harder time with it.

“It was getting real strange,” Helm wrote. “We’d never been booed in our lives. As soon as they saw the drums set up during the intermission, it was like, ‘Light the kerosene!’ Sometimes the booing would get to me, especially when they’d throw tomatoes or whatever, and my drums would get stuff on them. A couple of times, when I thought Bob wasn’t looking, I’d give ’em the finger.”

Helm said two particularly bad shows in Boston made him wonder if he could continue playing for angry audiences.

“We were seriously booed during a two-night stand at the Back Bay Theater in Boston,” he wrote. “That’s when it started to get to me. I’d been raised to believe that music was supposed to make people smile and want to party. And here was all this hostility coming back at us.”

Still, the Hawks continued playing with Dylan until 1967. At that point, they began recording their own songs under the new name, The Band.